I can't say for a fact that Nashville is still referred to with this nickname—in fact, I highly doubt it. But, "the Powder City" was highly applicable to Nashville's contribution to World War I. This was during a time that's distant from now, 100 years ago to be exact, and it was thanks to the Old Hickory Munitions Plant built by the DuPont Company. Yes, the same site that's there today, except it's no longer a munitions plant.

While the Old Hickory plant has been around for an impressive 100 years, the company itself has been in operation since 1802 when founder Eleuthère Irénée (E.I.) du Pont broke ground on the first powder mill location, along the Brandywine River near Wilmington, Delaware. It's a company that's embraced the concept of change and innovation throughout the past 215 years as a developer of some of the world's most advanced materials, including black powder, Rayon, Dacron polyester, artificial rubber (originally "DuPrene"), nylon (and several other materials ending in "on"), and a variety of other diversified chemicals that I can't begin to explain. But they're important!

While I wish I had the time to recap the history of the company, it's really the Old Hickory site that I'm planning to discuss. And it's definitely a location that serves as a prime example of the company's ability to adapt to the changing times. Before you read the brief (as brief as I could get it) history of the company, check out the slideshow of photos, clippings, and various other documents from the company's storied past in Old Hickory.

Disclaimer: In the various clippings and research materials I've viewed in writing this post, I've seen the spelling of the company name two ways - Du Pont and DuPont. I've used it both ways based on where I've pulled the information from. So if I'm wrong, I apologize. It did appear to start as "Du Pont" though.

"The Single Most Significant Economic Impact of the War"

The city of Old Hickory, formerly known as Jacksonville, was first targeted by DuPont in 1917 when it became likely that the U.S. would be entering World War I, and the need for munitions would be demanded. The federal government ordered the company to begin working on the site for the world's largest smokeless powder plant, but due to a few financial and administrative disputes, construction on the plant was delayed until the following March (1918). You probably wouldn't have noticed the delay however, because the plant was built in 4 months by 75,000 men on 5,600 acres, in Hadley's Bend.

The plant in Old Hickory went into operation on July 2nd, 1918 (approximately 121 days ahead of schedule). According to Don H. Doyle, author of Nashville in the New South, 1880-1930, the E.I. Du Pont Nemours Company (name shortened to simply DuPont in the 1920's) coming to Old Hickory was the single most significant economic impact of the war.

"In its scale and the speed with which it was organized, the Old Hickory Munitions Project eclipsed everything that came before it."

“War waved its red wand over a peaceful countryside,' one observer noted, 'and an industrial city sprang up as if by magic.”

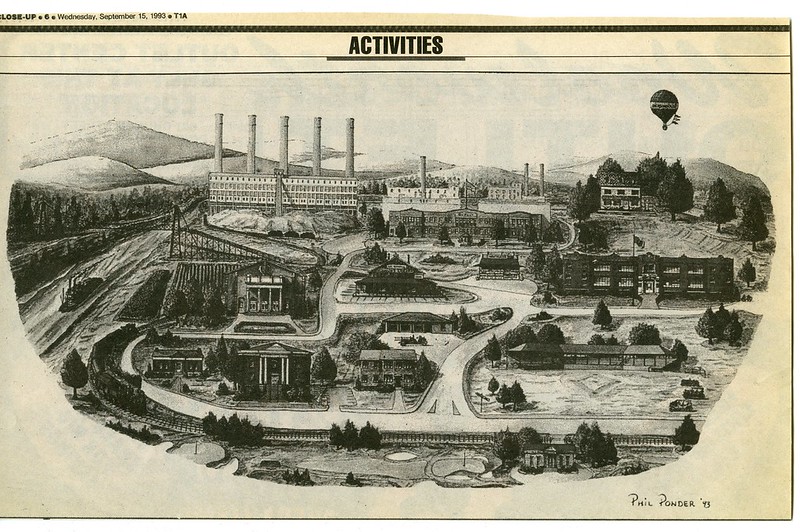

The city known as Old Hickory Village housed the 35,000 people who worked at the plant. According to the company's history page, the village and plant included 3,867 buildings and 7.5 miles of double-tracked railroad. In the artist rendering below by artist Phil Ponder, the town of Old Hickory is depicted as it was in 1918. The title of the drawing is "Old Hickory Reflections."

The building of the plant was impactful to the local economy in a variety of ways; it wasn't just a significant contribution to the war effort. Real estate values boomed and there was a surge in shopping in downtown stores, which offered special hours to Old Hickory residents.

However, with all the good that came with the munitions plant, there was also the bad. Doyle discusses in his book that the plant drained the local labor supply simply by offering higher hourly wages and the opportunity of independence and adventure in this new work place. On top of that, the surge of people flocking to Old Hickory brought other issues—lawlessness, racial violence, and health problems (most notably the Spanish Influenza in September, 1918). As I said, with the good comes the bad.

At least there was some good that came of the draining of the labor supply. According to Doyle, "though local employers bemoaned the destabilization of the labor force at the time, the DuPont plant helped to create an indispensable ingredient to the industrial and clerical work force that would be required by Nashville’s postwar economy.”

At the end of the war, the workers celebrated with the rest of Nashville despite the fact that the end of the war meant that the plant was no longer needed. A parade of trucks made up of floats were created by workers in celebration. Some of the workers (and their floats) even went downtown where all the action was to join the parade in progress there. One worker noted that: ”...all of Nashville was wild with joy and they gave us a great ovation.”

Post-Great War years and "Rayon City"

Another interesting piece of information, albeit sad, that I stumbled upon regarding the munitions plant is that it was the destination for some of the passengers on the No. 1 train coming from Memphis to Atlanta on July 9th, 1918. This was one of the trains involved in the worst passenger rail accident in U.S. history, at Dutchman’s Grade in Belle Meade (stay tuned next summer when I'll publish a blog post for the 100th anniversary of this crash).

After the war was over and Nashville began to enter a time of industrial limbo, the Du Pont Plant and the city of Old Hickory became a ghost town. The population of Old Hickory dropped from 35,000 to 500. However, according to Doyle, “the postwar years in Nashville were a time of vigorous growth, despite the city’s failure to sustain an industrial boom.”

The federal government no longer saw a use for the plant, and intended to junk/sell it. There were some who disagreed with this plan, including Congressman Joseph W. Byrns, who saw the plant as a great advantage to Nashville's industrial development. Alas, the Federal Government sold a portion of the land to the Nashville Industrial Corporation (NIC for short), a group of local business investors organized by the Commercial Club (the Club later changed its name in 1921 to the Chamber of Commerce). The NIC planned to develop the park for smaller firms; this primarily included industries from the North that saw an advantage to the area's cheap, non-union workers.

Du Pont decided to partake in this industrial party in July of 1923 when they announced that they'd be returning to build a $4 million dollar plant for the manufacturing of Rayon, an "artificial silk." Like gunpowder, Rayon also used cellulose. Picture below is of the Du Pont Rayon Company in Old Hickory, in 1929.

Textiles were something that Du Pont decided to include in their product line prior to the war, so it seems like an easy transition for them. To be specific, prior to the war, Du Pont had already broadened its products to other needed materials, including plastics, coated fabrics, dye-making (which later led to the modern organic chemicals industry), and as I already mentioned, textiles. In 1920, Du Pont acquired the Viscose Rayon process from a French firm (Comtoir des Textiles Artificiels) and created the Du Pont Rayon Company (previously the Du Pont Fibersilk Company).

The swiftness in building their first plant in Old Hickory carried over into the building of this new plant as well; just 9 months after ground was broken, they began production of the popular new fabric that mimicked silk without the high cost and Old Hickory became "Rayon City." By 1927, after the company had expanded several times, the Du Pont Rayon company had invested about $12 million in Old Hickory. Some of the original buildings that remained from the munitions plant were used for administrative purposes on the new site, and remained there until the 1960's.

"Better things for better living - through chemistry...."

1929 seemed to be another pivotal year for the plant and the city of Old Hickory. Du Pont announced that they'd be adding a cellophane plant to the site for another $3 million. In September of that year, the first sheet of cellophane rolled off the casting machine at the Plant, making it the 2nd plant to produce cellophane. Also, the county built the Old Hickory Bridge, linking the factories and the city together, symbolizing the new importance that the city played in Nashville's economic growth.

The downside to the company's success came around in the 1930's when the Du Pont brothers were given the nickname of the "merchants of death" and were investigated for war profiteering during World War I. This led to the 1934 U.S. Senate (Gerald P.) Nye's Committee hearings of which no evidence was ever found to corroborate the charges. But the dislike of the company by the American public didn't end there due to the fact that the Du Pont brothers were also prominent opponents of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the "new deal." Amidst all of this, the company continued to succeed as the second largest family-run firm in the world.

According to the company's history page, by 1937, Du Pont was producing moisture-proof cellophane film at Old Hickory as well as 4.2 million pounds of yarn a year. Just like the first World War, the 2nd World War provided more opportunities for the company to expand. This meant that by 1946, the physical site now included the plant facilities, a housing development, and a golf course. And why not?

To help wrap things up a bit, here are a few other highlights of the Old Hickory plant's history:

- Sometime at the end of 1945, a kitten by the name of "Skizzafrinna" is adopted by the workers in the Plant 2 Spinning Room (I thought this was very important to share as part of the company's history).

- In 1951, Old Hickory's residents took over control of the town from Du Pont.

- The product Dacron (a synthetic polyester) replaced Rayon operations in the 1960's.

- The introduction of new products: DMT (which may or may not be the same thing as Dacron, haven't been able to figure this out) in 1960, Reemay and Corfam in 1965, Typar in 1966, Sontara in 1973, and Crystar in 1987. In 1961 and 1964, Rayon and Cellophane cease operations.

- In 1976, a new DMT facility is operational and the Credit Union announces plans to open new building near the entrance to the plant.

- In 1982, after 21 years, yarn production ceases.

- In 1985, to celebrate the plant's 60 years of operation, a time capsule was installed in a monument near the plant entrance.

- In 2002, the company celebrated its 200th birthday.

More details are included in the Old Hickory site's timeline here:

As of today, the site in Old Hickory is not quite what it once was, but the company is still there. According to an article written in the Tennessean in August of this year, the land originally owned by DuPont has been and may continue to be subdivided, to create a "multifaceted industrial park." Most recently, 25 acres were sold to a railroad company for $1.2 million. The company will be celebrating Old Hickory's centennial next summer, since it was in July, 1918 when the munitions plant began their work.

All the information I used in this post are from clippings we have here in Archives, the book I mentioned - Nashville in the New South, 1880-1930, and the company's website. Tennessee State and Library Archives also has a collection of photographs from the plant's early days. If you're interested in learning more, I encourage you to give us a visit.

And I'll leave you with this - from all of us here at Metro Archives, Happy Holidays!